Here are some of my rough notes on OVSDB and hardware VTEP.

The Rise of Virtual Networks

With the advent of Software Defined Networking (SDN), new networking capabilities are opened up to an organization. Just imagine being able to programmatically request from your provider a two-fold increase in your bandwidth between 10 AM and 12 AM today when you will need to send a bulk of data offsite and then paying only extra for that increase within that time. It’s an exciting time for networking as it finally completes the utility-based computing we’ve been talking about for years now. Granted we can’t do that quick bandwidth burst as of today, but we’re getting there.

In the meantime…

There’s this issue of existing workloads on physical machines in traditional networks that need to join the SDN party. Some of these workloads we can move to virtual machines so they can join the virtual networks, but some of them we just can’t for various reasons, technical or otherwise. As a result, virtualized workloads can’t access resources from traditional ones and vice versa. One of the earlier solutions was to use a software gateway (typically an instance of Open vSwitch) that sits between the traditional and virtualized networks routing traffic to the correct destination. This did the job for light to moderate traffic but turned into a bottleneck for workloads beyond that.

Enter VTEP

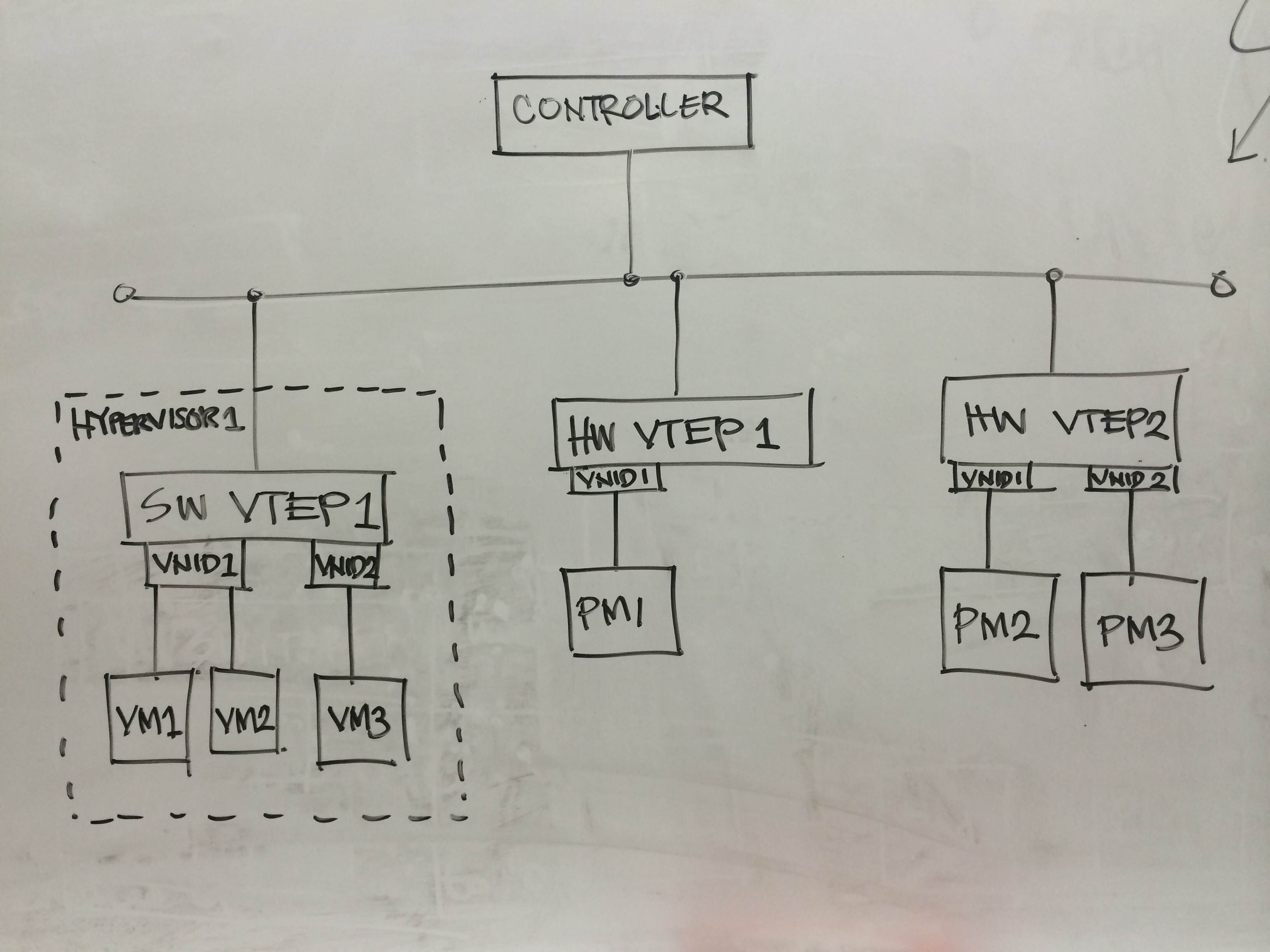

VTEP stands for Virtual Tunnel Endpoint and is a essentially a hardware device (e.g. A switch with VXLAN capabilities) or software appliance (e.g. Open vSwitch) that is capable of encapsulating packets with VXLAN headers. Let’s explore this further with a diagram:

In the above diagram, we have three VTEPs on the network where one is a software implementation (e.g. Open vSwitch) while the other two are physical switches that understand VXLAN. As a whole, we can see that these VTEPs know about two virtual networks designated by VNID1 and VNID2. VNIDs are VXLAN Network Identifiers. Quoting Cisco’s VXLAN Overview: “VXLAN uses a 24-bit segment ID known as the VXLAN network identifier (VNID), which enables up to 16 million VXLAN segments to coexist in the same administrative domain.”

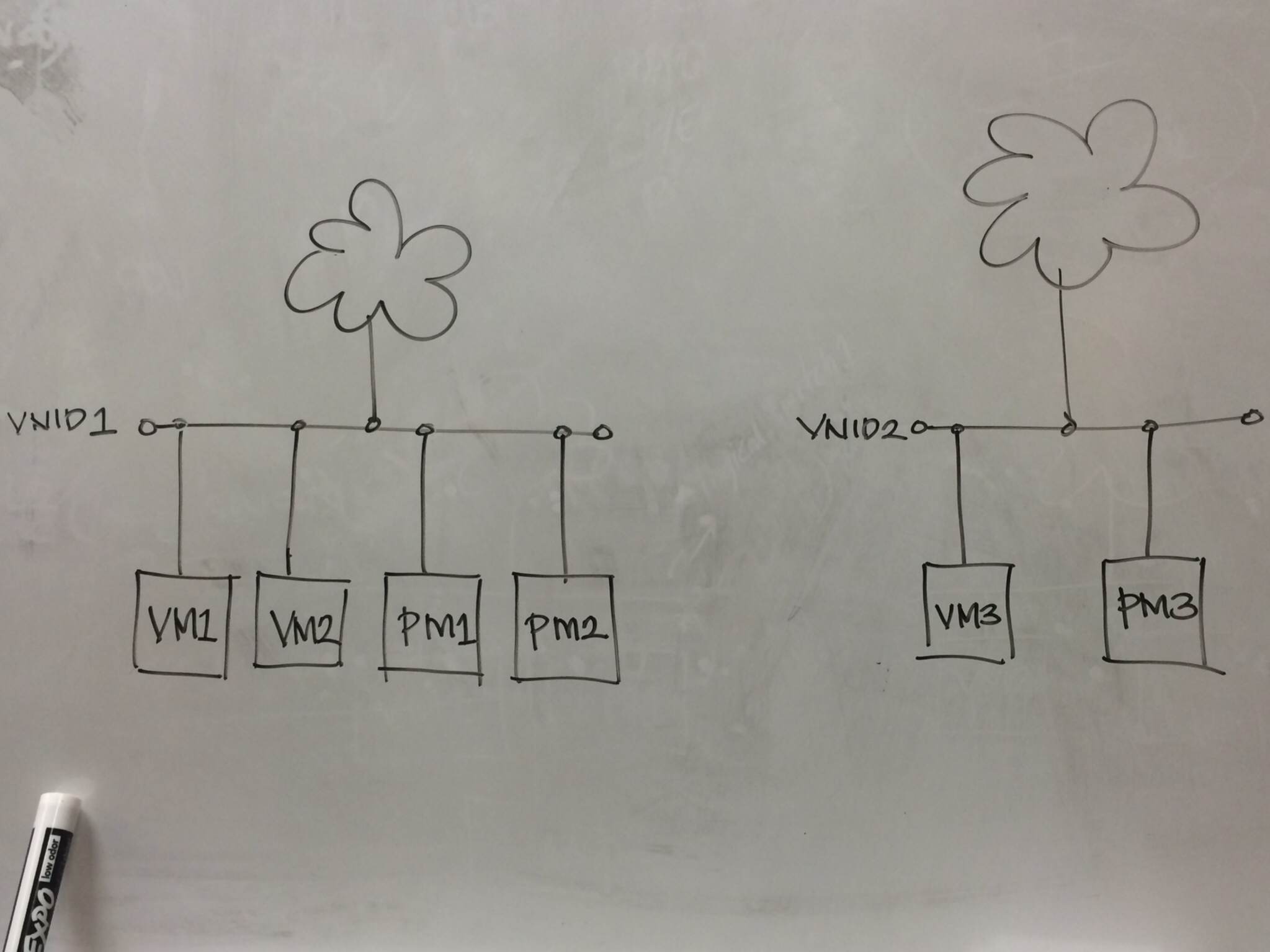

The result of this is that from the point of view of the virtual and physical machines, these are their networks:

There’s more to this than what I’m covering, obviously and I don’t claim to be an expert in this domain so I highly recommend clicking on my references below for more information on VXLAN.

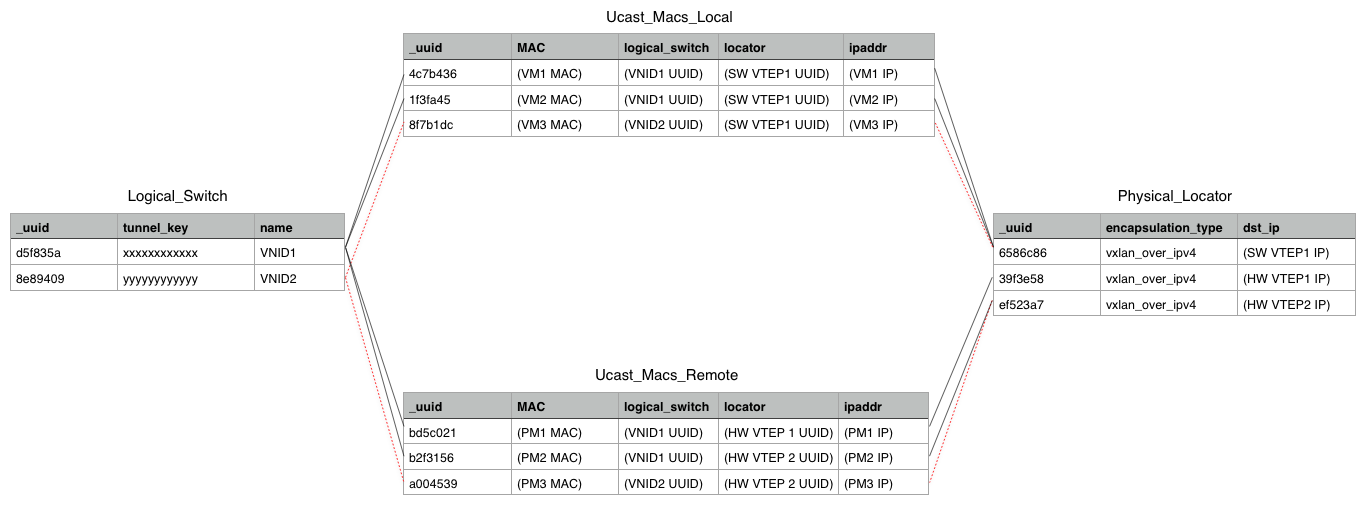

OVSDB and the hardware_vtep schema

I’ve been playing around with OVSDB and the hardware_vtep schema and this is what I’ve learned so far. For this example, let’s assume we’re inside of SW VTEP1 in the diagram above.

A summary of the above tables:

- The VTEP keeps track of machines connected to it via the Ucast_Macs_Local table

- Each row is associated with a VXLAN as specified by the logical_switch column

- Each row is also associated with a VTEP which, in this table is always SW VTEP1

- The VTEP also keeps track of machines in other VTEPs via the Ucast_Macs_Remote table

- Each row in this table is also associated with a VXLAN as specified by the logical_switch column

- Each row is also associated with a VTEP which, in this example, may be one of the two HW VTEPs

There are other tables in the hardware_vtep schema such as Mcast_Macs_Local and Mcast_Macs_Remote. For more information, see the reference to the hardware_vtep schema below.