If you’ve ever worked with Jenkins shared libraries, you know that they’re a great way to simplify your Jenkins Pipeline DSL scripts by abstracting out common code to a function. For example, this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

stage('Prep') {

script {

// Create the release ID for this build

def version = readFile('VERSION').trim()

def buildID = env.BUILD_ID

def shortSha = env.GIT_COMMIT.take(7)

def prMetadata = ''

if (env.CHANGE_ID) {

prMetadata = "pr${env.CHANGE_ID}."

}

env.releaseID = "${version}+${prMetadata}.b${buildID}.${shortSha}"

}

}

Could become this:

1

2

3

4

5

stage('Prep') {

script {

env.releaseID = getReleaseID()

}

}

And you also get the added benefit of being able to re-use that same function in your other pipelines. Very important in this era of microservices where each microservice has a pipeline of its own.

The Problem With Shared Libraries Though…

Is that they’re awesome once you’ve got them working the way you want. While you’re still working on your library, however, it’s a major pain to write code, commit to your repo, push upstream, then trigger some test pipeline only to see that you committed some syntax error or you forgot to close a bracket or you fat-fingered a function. so now you have to do that all over again, and again, and again until it’s just right.

What if you could employ TDD on your workstation so that you can catch minor errors and regressions immediately? What if, as soon as you push your changes upstream, Jenkins runs the same unit tests so that you and the rest of your team can be on the same page about the state of your shared library?

That’s what we’ll be learning about in this blog post. So if you want to regain a little bit of sanity when managing your Jenkins pipelines, keep on reading!

Your Library’s Structure

.

├── src/

│ └── org/

│ └── yourcompany/ # This is where most of your code's logic will go

│

├── test/

│ └── org/

│ └── yourcompany/ # This is where your unit tests will live

│

├── vars/ # This is where your global functions (aka global vars)

│ # will go. Functions written here will be the ones

│ # we'll use in our pipelines.

│

└── pom.xml # This is where we'll configure our test executionSome Dependencies

We’re working with Groovy and, therefore, Java and friends here so we’ll need a few things installed in your local workstation and on your Jenkins workers:

- Java JDK 8 (this will mostly likely already be installed in your Jenkins cluster)

- Groovy 2.4.12 or higher

- Ensure that your

GROOVY_HOMEandJAVA_HOMEenv variables are set - Maven 3.5.2 or higher

Your pom.xml

I’ve read of different ways to get your pom.xml to work just the way you want it to but I’ve had to massage mine so that it can run the tests and produce JaCoCo data that I can use in Jenkins. Here’s what mine looks like. YMMV. I’ll also provide references to my sources at the end of this blog.

Designing Your Shared Function

When designing a new class or object, your first step should always be to think about its API, its responsibilities, and its collaborators/dependencies. Those same steps remain useful in this case so I highly recommend doing that. For this blog, we’ll re-use the example I provided at the top of this page.

1

2

3

4

5

stage('Prep') {

script {

env.releaseID = getReleaseID()

}

}

In this case, we want to call getReleaseID() and expect it to return

a release ID for the current build such as 0.1.0+b23.83575a2 or

1.6.1-dev+pr123.b982.7eaa8db (assuming you’re using Multi-branch pipelines

and you should!)

Drafting Our Shared Function

Let’s write the global var/function in our vars/ directory now. Remember

that we want this function to be as thin as possible so that we can test as

much of our code as possible. To provide the above API, we’ll write our

vars/getReleaseID.groovy like so:

1

2

3

4

5

6

import org.yourcompany.ReleaseIDGenerator

def call() {

def generator = new ReleaseIDGenerator(this)

return generator.generate()

}

Like I said, as thin as possible. Also note that we should consider this a

draft for now and is only meant to guide us as we write our unit tests for

our actual code which will now reside in the ReleaseIDGenerator class.

Using Mandatory Dependency Injection To Our Advantage

Notice line 4 above how we’re passing this to ReleaseIDGenerator’s constructor.

This is necessary because the objects instantiated from ReleaseIDGenerator

will have a different context from our pipeline script and so it won’t have

access to sh or echo and so on. However, since our global function

getReleaseID has the same context as our pipeline script, when we pass

this from there, we’re actually passing your pipeline script’s context to

our class. The latter part is a good thing because we don’t need to require

our shared library’s users to remember to pass this everytime they call

getReleaseID().

An even bigger plus about this dependency injection is that we can use that to mock or stub out the pipeline script when running our unit tests! Let’s see that in action next.

Let’s Write The Test First

This will be the initial contents of test/org/yourcompany/testReleaseIDGenerator.groovy

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

package org.yourcompany

class ReleaseIDGeneratorTest extends GroovyTestCase {

// We're stubbing out a pipeline script. This one pretends to be

// a script that's running against the master branch.

class MasterPipelineScript {

def version = ""

def requestedVersionFilename = ""

def env = [

'BUILD_ID': 15,

'GIT_COMMIT': 'a3bb4b7f9bf5db1c436b96a970c04d553feed1c5'

]

def readFile(versionFilename) {

this.requestedVersionFilename = versionFilename

return this.version

}

def MasterPipelineScript(version) {

this.version = version

}

}

//

// Tests

//

void testMasterPipelineHappyPath() {

def version = '1.2.3'

def pipeline = new MasterPipelineScript(version)

def shortSha = pipeline.env.GIT_COMMIT.take(7)

def expectedReleaseID = "${version}+b${pipeline.env.BUILD_ID}.${shortSha}"

def returnedReleaseID = new ReleaseIDGenerator(pipeline).generate()

assert 'VERSION' == pipeline.requestedVersionFilename

assert expectedReleaseID == returnedReleaseID

}

}

Let’s break this down:

- Lines 7 to 24 is just a plain old class that we’ll use to stub out just enough of a pipeline script that our test subject needs to do its job.

- Lines 30 to 40 is our actual test

- Line 32 is where we’ll instantiate our stub pipeline and make it pretend

that the contents of the version file is

1.2.3 - Line 36 is where we’ll exercise our test subject

- In line 38 we check to make sure it actually tried to read the correct file to get the version.

- In line 39 we check to see if returned the release ID that we exected

That’s it. We now have our first unit test. Run mvn clean install should

get you a report saying your test failed. Now it’s time to write the code

to pass the test!

Our First Class

Here’s our src/org/yourcompany/ReleaseIDGeneratory.groovy

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

package org.yourcompany

class ReleaseIDGenerator implements Serializable {

def script

def ReleaseIDGenerator(script) {

this.script = script

}

def generate() {

def version = script.readFile('VERSION').trim()

def buildID = script.env.BUILD_ID

def shortSha = script.env.GIT_COMMIT.take(7)

return "${version}+b${buildID}.${shortSha}"

}

}

Running mvn clean install should now get us a passing test as well as a

JaCoCo exec data file in the target/ directory that we can use when

we run these tests on Jenkins.

Configuring Your Shared Library

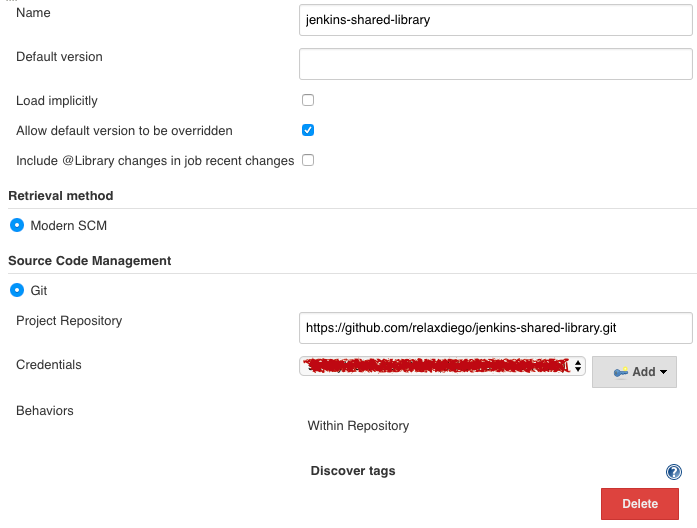

You don’t need this step if all we want is to run the unit tests on Jenkins but it’s a good idea to do this now to avoid any weird issues down the line. This shared library should be configured in your Global Configuration page this way:

One of the important parts above is that “Load implicitly” must be unchecked so that Jenkins doesn’t load the library on the pipeline script that’s going to be testing the library!

This will also mean that you’ll have to include the following line in your application’s Jenkinsfile:

@Library(jenkins-shared-library@master') import org.yourcompany.*

That’s not a big deal though compared to the benefits that we’re getting from having an automated pipeline for our pipeline’s libraries!

Let’s Define the “Meta” Pipeline

So now we need to create a Jenkinsfile for our shared library so that Jenkins can run the unit tests and report on code health for us.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

pipeline {

agent any

tools {

maven 'Maven 3.5.2'

}

stages {

stage ('Initialize') {

steps {

sh '''

echo "PATH = ${PATH}"

echo "M2_HOME = ${M2_HOME}"

'''

}

}

stage ('Build') {

steps {

sh 'mvn -Dmaven.test.failure.ignore=true clean install'.

}

post {

success {

junit 'target/surefire-reports/*.xml'.

jacoco classPattern: '**/target/classes',

execPattern: '**/target/coverage-reports/jacoco-ut.exec',

sourcePattern: '**/src/org/yourcompany',

exclusionPattern: '**/target/classes/*closure*.class'

}

}

}

}

}

Commit that to your repo, push it to origin and now you should have the beginnings of a unit tested shared library! All you need to do is go to Jenkins, create a Multibranch pipeline and then make sure that your git repo will call its webhook. Once you have that in place, you’ll have Jenkins automatically run your unit tests and report back on your pull requests or even direct pushes to origin/master or whatever remote branch you’ve configured your pipeline to watch.

This Isn’t a Silver Bullet

Just remember that the ability of this method to catch errors will be limited

to syntax error and implementation bugs. It won’t be able to catch errors in

how our global function call our code in src/ and it won’t be able to catch

errors in your pipeline script (Jenkinsfile). But the benefits that it provides

far outweight the minimal learning and setup that you need to get it up and

running so I definitely recommend getting this in place.

Prior Art

I’m not the first one to do this kind of thing. Here are some references that helped me along the way:

- Jenkins’ global shared pipeline libraries (real) unit testing

- How to put your entire pipeline on your shared library

All the Code

- Stuff I wrote up there are down here