Preamble

This article attempts to cut through the cruft and re-discover what it really means to practice DevOps in your organization. It does this by reviewing the three principles of DevOps: systems throughput, fast feedback, and continuous learning. It further re-inforces these principles with two tried and tested engineering concepts: The Theory of Constraints and Control Theory.

TL;DR

DevOps is just Process Engineering specialized for software delivery. The wealth of knowledge built up by Process and Industrial Engineering will prove useful in delivering software products.

Let’s Dismantle Pre-existing Notions

Whenever I try to define foundational concepts, I find that it’s more effective if I start by specifying what the concept is NOT about. As an analogy, consider the process of building physical foundations. If you want to ensure that the one you build is solid, you’ll want to dismantle any pre-existing ones that might be incomplete, incorrect, or generally unstable. It’s the same with foundational concepts: in order for them to take root in your mind, we must destroy any pre-conceived notions that might prevent them from doing so.

So let’s start out by defining what DevOps is NOT.

WARNING: the following text may be controversial but hear me out for a bit and I assure you it will be worth your time.

DevOps is not about automation

That may sound crazy but think about it for a second. If you start out with this mindset as the primary goal of DevOps, then you run the risk of pursuing various automation projects that don’t have a common goal. In this case, automation for the sake of automation is like a sailboat that’s favored by the winds but doesn’t have a rudder to guide it–you’re just going nowhere fast.

DevOps is not about bringing Dev and Ops together

If all you’re doing is coaxing them to work within the same room (physical or virtual) and going “OK, you guys are a team now. Play nice.” That’s just like lighting up a bunch of firecrackers and mixing them together in a big tub. It may be exciting to watch but that’s likely not going to get stuff done. Dev teams and Ops teams are generally passionate about the work that they do and there will always be some tension between these groups. Left unmanaged, it will just add fuel to a wildfire.

DevOps is not about increasing team velocity

If you make this your primary objective, you run the risk of eventually confusing working long hours and sleepless nights as “doing DevOps.” I’ve seen this enough times to know that it’s easier to confuse these two than people would like to admit and I’ve also learned that it’s quite a slippery slope that quickly leads to team demotivation and burnout.

Well, OK maybe DevOps is…

So, have I shaken your pre-existing notions of DevOps yet? I did say in the beginning that I will try to destroy any preconceived notions of DevOps in your head. I imagine that must have been jarring to read so let’s go straight to re-building that foundation.

First, let’s relax the things that I just said:

- DevOps is not just about automation

- DevOps is not just about bringing Dev and Ops together

- DevOps is not just about increasing team velocity

What I’m saying is not that automation, bringing Dev and Ops together, and increasing velocity have no place in DevOps. They certainly do. However, these alone are not enough to support your organization’s DevOps initiative and they’re certainly not the foundations. Instead, they are approaches that need to be supported and guided by a solid foundation in order to work.

The Foundations of DevOps

For this part, I’m going to guide you through two major sections. First, we will talk about the 3 principles of DevOps. Second we will reinforce these 3 principles with two tried and tested engineering concepts that have been around since the 1800s and these engineering concepts permeate our everyday lives whether we realize it or not.

Alright so let’s tackle the first major section!

The 3 Principles of DevOps

This section derives the principles from the work of Patrick Debois, Gene Kim, and Jez Humble. Specifically from their seminal book titled “The DevOps Handbook” first published in 2016.

The First Principle

The first principle has to do with viewing throughput at a systems level. You’ll recall that the general definition of throughput is the rate at which something (a person, a team, an organization, etc.) is able to complete a unit of work over a given period of time. In IT, when we think about systems throughput, we might be talking about actual value delivered to the customer per week or month. When we say value, it’s a software feature or enhancement that the customer deems useful, accessible, and working as expected. So this principle says that you must design your processes such that you optimize for this type of throughput.

That is: all your decisions and actions as an organization should revolve around ensuring you deliver working features and enhancements at a consistent and optimal rate given your current resources.

Already the first principle alone will raise a lot of questions in your head. Hopefully those questions are about how well your organization is optimizing its throughput and what are the factors that affect throughput. If so, then you’re on the right track. I would encourage you to write down these questions so you can revisit them later.

The Second Principle

The second principle is fast feedback. That is, timely access to the results of an action taken within the system and, just as important, this information must be accurate. This second principle says you must design your organization such that feedback is actually fed back to your engineers as soon as possible, not to punish or shame them, but to aid them in course correcting as soon as possible.

I can’t emphasize this part enough: the feedback must be non-threatening to the recipient. Too often managers abuse this feedback as a way to scare engineers into doing their job correctly. This misses the point and actually undermines the foundation upon which you want to build your DevOps practices.

We’ll get an even better understanding of why non-threatening feedback is important when we talk about the next principle. For now, think about implementing fast feedback in your organization as an extension of how an IDE informs engineers of implementation errors. When an IDE reports a syntax error, for example, it’s factual, non-threatening and gets to the point so that the engineer can go straight to debugging and fixing the error.

I hope that gave you a good enough introduction to the second principle and, as with the first principle, I hope it brought up a number of questions in your head, hopefully along the lines of “how do we implement fast feedback that is factual, non-threatening, and actionable? If so, then you’re on the right track.

The Third Principle

The third principle is about continuous learning and experimentation or the ability of the system to capture external information, feed that back into the delivery process and use it as a way to be able to tell the difference between what was intended and what actually happened. The main purpose of all this, of course, is so that one can quickly change course as needed. This third principle ties in very nicely to the part I said earlier about non-threatening feedback.

Now a deep dive into the effects of a psychologically safe environment on organizational learning is outside the scope of this article and I’ll let you do the Googling for yourself to fact check me but for now, it should suffice to say that a non-threatening, psychologically safe environment has a positive effect on continuous learning and experimentation.

As with the other two principles, I hope this also made you think about how to design an environment that is conducive for continuous learning and experimentation. If so, then you’re on the right track and I commend you for doing a great job of keeping up. Go ahead and write down your questions before we proceed to the second section.

The Two Engineering Concepts Behind the DevOps Principles

The 3 DevOps principles sound good and quite actionable but you may still be wondering if this is just another consultancy scheme like all others that have come before it. If so, I don’t blame you. I myself have been burned many times before by process engineering gurus that promise to fix all your operational problems if you just pay for their bestsellers and thousand-of-dollars training courses.

So this section is about showing you that the three DevOps principles were not invented by Patrick Debois and company out of thin air. These principles actually build upon two tried and tested engineering concepts that date back as far as the 1800s. Let’s now take a deeper look into these 2 engineering concepts:

The first one will talk about is the Theory of Constraints which was established in the 1970s by Dr. of Physics Eliyahu Moshe Goldratt. While the second concept is Control Theory which was established in 1868 by physicist James Clerk Maxwell

Theory of Constraints

The Theory of Constraints is best summarized by the idiom “the chain is no stronger than its weakest link.”

Expanding from that idiom, the Theory of Constraints guides you in looking for the weakest link, in monitoring that weakest link, and finally managing that weakest link. By doing so, the Theory of Constraints helps you ensure the integrity of your system.

The Theory of Constraints does this by using three metrics but I want to focus on the first one because, from how I understand it, this metric actually determines the other two. The metric that I want to focus on is Inventory. Recall that inventory is basically an organization’s money that’s been “frozen” into “a thing” or “a bunch of things” that is in the process of being converted into a sale that will generate more money for the company. Some of you, especially those in the professional services sector, might be wondering “what inventory? we don’t have inventory.” In a limited sense that’s true but you have to consider that there are actually different types of inventory and the type that’s common to all IT organizations is Work In Process (WIP) inventory.

WIP is identified by the TOC as inventory and, in fact, it’s one of the most important types of inventory because it’s the one standing in the way between a company and its potential revenues. And, to add to that, WIP inventory is easily overlooked by organizations because it tends to be not as visible as other types of inventory.

Alright this is all interesting but I’m sure that, so far, I’ve opened up even more questions than answers in your head so let’s go straight to a concrete example of how WIP management can directly affect a team’s throughput. What I’m about to show you are the results of a ToC workshop that I facilitated a few years back in a previous employer. This workshop was attended by a group of managers. Our objective was to find a job scheduling process that would help make job delivery more predictable:

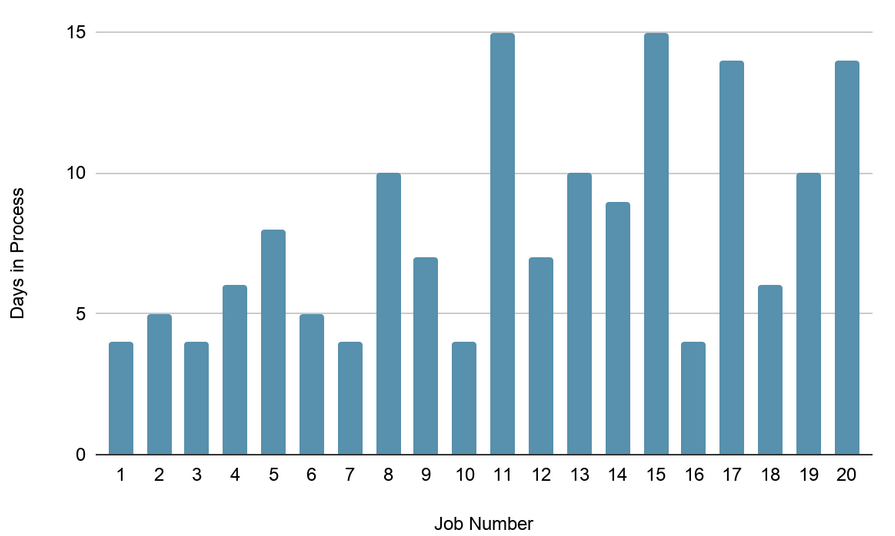

First we tried “no scheduling”: Input jobs as they come. We had a fixed stack of jobs and the managers were instructed to randomly shuffle the stack. This was the result.

So what you’re looking at is a chart that tells you how long each job took to finish. On the X axis, you’re looking at the job number which also correlates to the day the job was introduced. On the Y axis you’re seeing the actual number of days it took to complete the given job. You’ll notice that as time passes by, the variability of job delivery times increases. That’s not the most interesting part. The most interesting part is that each of these jobs are actually equally sized. That means each job will go through exactly 4 job stations on the way to completion and each job station will spend 1 day per job.

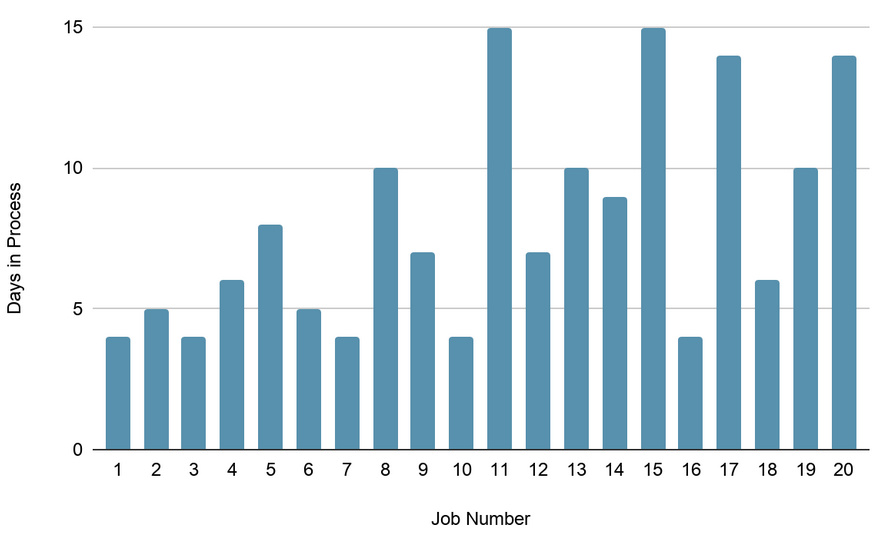

Next we tried prioritizing using exactly the same set of jobs as in exercise 1. The managers discovered that station 2 in the process was a bottleneck because there were some types of jobs whose flow was Station 1, Station 2, Station 3, Station 2, End. The managers looked for those types of jobs and worked together such that the jobs were prioritized in a way that lessened that congestion. This is the result after that exercise:

As you can see, it doesn’t look any different from the results of the first exercise.

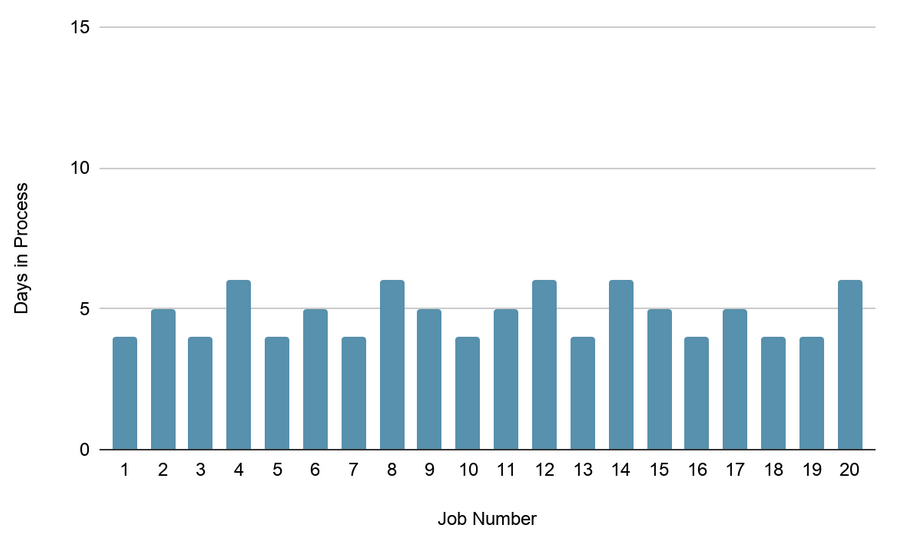

Finally we tried a ToC method called Drum-Buffer-Rope (DBR) which basically says add a buffer in front of your constraint and only introduce a job such that the buffer in front of your bottleneck has a nearly fixed amount of jobs waiting for its job station to process. There’s more to DBR than this but let’s cut to the chase and see what the results were:

The results were astounding. By just doing this simple thing of basing your actions on the WIP in front of the bottleneck we greatly reduced variability and improved flow. And by the way, to be able to compare apples to apples, we used the same set of jobs AND arranged them the way they were arranged in exercise 1.

Applying ToC and DBR to IT

So this is why, in Kanban, you must limit the number of tasks in a given column based on the number of people that can work within that column (or job station). If you’re using a Kanban board but not using column constraints and not actively managing WIP in the board, it’s not really Kanban and you’re not achieving flow.

This is also why, in a well-designed CI/CD pipeline, the end-to-end testing phase (which normally takes a long time to finish) implements a LIFO queue (or buffer) which drops the older items in the queue upon pulling out the latest job. If it doesn’t do this, WIP in the pipeline balloons, flow (aka throughput) drops and we end up with an excruciatingly slow and unreliable pipeline. Some teams resort to the wrong approach of moving long-running tests to a nightly build which breaks the 2nd principle of DevOps (fast feedback) because now you have to wait until tomorrow to get feedback on the work you did today.

Sidenote: I talked about implementing a LIFO queue in a pipeline in this article.

Let’s take it one step further and bring this lesson to the networking domain. This is why managing the buffer size of a router is an important aspect of networking and that the FIFO queueing system will start dropping packets when the queue is full: to keep WIP at a manageable level and maintain constant network throughput as much as possible.

I suppose the next question in your head is this: what is our point X, our constraint, in the delivery process and how do we monitor it? If so, that’s a great starting point and I encourage you to pursue that further because that will lead you to excellent ideas for optimizing your delivery process.

For now, let’s move on to the next part which talks about the second theory behind the 3 principles of DevOps.

Control Theory

Control Theory is best exemplified by this diagram:

Image source: Wikipedia

The relevant parts are:

- You have a desired outcome labeled as “Reference” here.

- That reference is fed to the Controller which then uses that information to instruct the System to do something

- There is then a Sensor that measures the actual effect or output of the System and feeds it back to the Controller

- The Controller then combines this feedback with the original reference to determine any difference and whether it needs to self correct or stay the course.

This is what is called a dynamic control system. So what’s the relevance of Control Theory and Dynamic Control Systems to us? Well it turns out that Dynamic Control Systems are all around us. For example:

Your home heating/cooling system is a dynamic control system where you feed it your desired temperature which its controller then uses to turn on the system. It then measures the room temperature and, based on that, will inform the controller whether to keep the system producing hot/cold air or turn it off to keep the room temperature within a certain tolerance.

For anyone who drives a car with dynamic cruise control. You tell it to keep a distance of 1 or 2 car lengths from the car in front and it accelerates or decelerates automatically depending on the actual distance between you and the car in front.

Let’s take an example that would be more relevant in the IT world: A well-designed CI/CD pipeline is a dynamic control system. Actually, it’s a series of mini-dynamic control systems but let’s just focus on the one at the end: the deployment part. You tell it to deploy a given version and also have set a tolerance for errors logged during the deployment. The system takes that information and starts deploying your new version. As it replaces each old instance of the old version with the new version, its sensors will feed it back any relevant errors encountered. If the error level is within the tolerance you set, it will continue to completion. If the error level breaches the tolerance, it will roll back the upgrade.

So what’s the takeaway from Control Theory and Dynamic Control Systems? A lot but the one thing I want you to focus on is the continuous collaboration between the Sensor and the Controller such that the entire system will self correct.

And again, I want to highlight the importance of a psychologically safe environment in a self-correcting dynamic system. In the examples above, the feedback returned to the controller doesn’t cause any panic, right? Otherwise the whole system will fail. This is the same whether the dynamic control system is fully automated or includes human intervention. You must ensure that every component that composes the Controller does not panic!

Sidenote: I talk about dynamic control systems in an agile organization in this article.

Recap

So that was a lot to take in. Let’s find a way to summarize everything so that we can internalize it and come up with actionable items later.

DevOps is about:

- Achieving optimal (not necessarily maximal) system throughput;

- Getting timely and accurate feedback for actions taken;

- Building an environment that is conducive to continuous learning and experimentation.

DevOps is backed by real engineering concepts:

- Theory of constraints which guides you in managing your work in process (WIP) inventory to ensure optimal team throughput;

- Control Theory which gives you a framework for collecting timely and accurate feedback and using that to self correct as needed.

Finally, DevOps can make use of automation and collaboration between Dev and Ops but they must be used under the guidance of the principles and engineering concepts stated above.

I hope that gave you a good enough understanding to jumpstart your career in DevOps. Good luck on your journey!